Have You Seen A ‘Teji’?

The stock market evoked mixed reactions through the last few months. Up until November 2020 when Nifty regained its previous highs investors watched in amazement and I am sure with a sense of relief. But my interactions suggest that the journey from breaching the previous high to crossing 15,000 in February has largely evoked disbelief.

Markets are markets and there are participants with varying length and quality of experience. But just as we keep India’s demography in the background for all kinds of business and markets or economic estimates, it would not be wrong if I estimated that 80-85 per cent of market participants today – as in unique investors in equities either directly or via mutual funds – have not seen a ‘Teji’. In fact, as per Zerodha, India’s largest stock broker, the average age of their clients is just 30 years which means that many of them have not experienced the previous ‘Teji’ phase between 2003 and 2009.

Let me clarify what is the ‘Teji’ I am referring to. ‘Teji’ is a Hindi word which signifies dynamism, speed and momentum all at the same time. Usually we describe market phases as ‘Teji’ and ‘Mandi’. Teji signifies a positive trajectory and Mandi the opposite direction or directionless if one is lucky. But the ‘Teji’ I am referring to in the header here is not the one that applies to stock markets – I am referring to ‘Teji’ as applied to the economy.

The Ebb and Flow of Sentiments

Coming back to the disbelief element, it is but natural given that the last few years have been full of false starts leading to sharp rallies in the stock markets pricing in an imminent GDP recovery and by implication in corporate earnings too.

In the first five years of the Narendra Modi-led NDA term, reforms were focused towards improving transparency in the economy, be it the anti-corruption agenda, repair of banking system including the IBC, and the demonetisation. Each of these reforms were significant but disruptive for growth, a fact which markets overlooked in continued hope of a recovery in the second half or the year after.

Thus, each time immediately after scaling new highs (March 2015, September 2016, January 2018), markets were weighed down by fresh bouts of uncertainty over growth materialising. Some of these corrections had global origins beyond the reach of domestic policies. For example, the Renminbi devaluation stunned the financial markets in August 2015 and by the end of February 2016, Nifty was at 6,900, down by 22 per cent from its March 2015 highs. Thus, by and large, between 2014 and early 2017, the Nifty kept oscillating in the range of 6,500 to 9,000 with intermittent rallies followed by panic and sharp corrections.

In 2018, the Nifty did scale past the 11,500 mark momentarily but that was short-lived as liquidity conditions tightened and oil prices rose to $90 a barrel. The subsequent IL&FS default set off a domino adversely affecting borrowing costs of NBFCs and private lenders. In the overhang of credit crunch and tight liquidity, GDP growth over the second half of FY2019 slipped below 6 per cent and by 2020 it was well below 5 per cent year-on-year.

The Nifty did momentarily scale the 12,000 level in the lead to the 2019 general elections but by September 2019 was back to 10,700 levels. Then finally it looked that the RBI and the government had decided to bring growth back into focus with an accommodative monetary policy and an expansionary fiscal policy. The fiscal policy was exemplified by way of substantial corporate tax rate cuts and the Production Linked Incentive (PLI) schemes to relocate manufacturing into India.

We could see the markets reflecting improving economic prospects by regaining 12,000 in January 2020 before the Covid outbreak took the Nifty all the way back to its 2014 election levels of 7,500.

Markets scaled new highs in February on the back of continuous surprises in economic data as well as a reforms-oriented budget. Subsequently there has been some softening in sentiments as the Covid cases began to rise again, although it is unlikely that the second wave will be as economically disruptive as the first wave.

Growth Slowdown Reflects in Earnings

What happened after that doesn’t need a recap but the following points emerge:

- In the last seven years, the economy has shown a promise to come back on rails many a times and the stock markets have rallied from time to time expecting ‘Karan-Arjun’ aka corporate earnings to also come back.

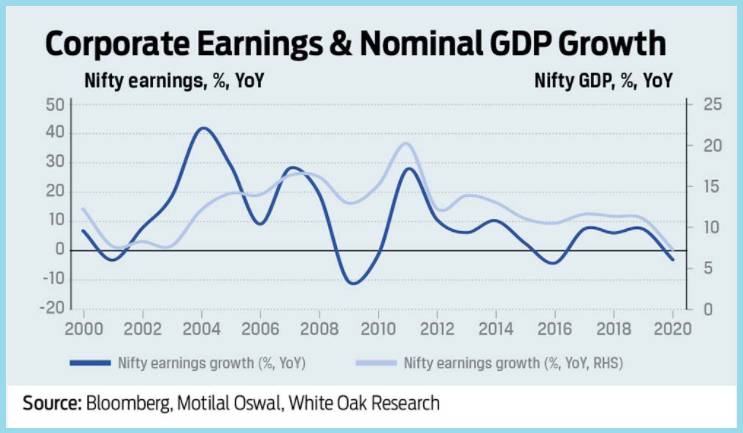

- Nominal GDP growth since the last five years has averaged 8-11%, down from 14% in the preceding five years. This is also reflected in the corporate earnings growth. (See the chart)

- Hence each of these ‘mere Karan-Arjun aayenge rallies’ has been followed by one or the other setback and a correction in the markets.

- Investors may enter at any time and seek liquidity any time, but in the last seven years even for a three-year or a five-year rolling period the end returns have been all over the place and even for these reasonable holding periods volatility has been high and averages poor.

- While earnings haven’t grown meaningfully or even stagnated, prospects of economic recovery have resulted in PE multiples on an aggregate being stretched.

Earnings Recovery: Not a Question of ‘If’ but of ‘When’

As an example, let’s take a time frame where corporate profit growth is 5 per cent annualised over a seven-year period so that from a starting point of Rs 10, EPS grows to Rs 14. Despite this kind of chequered past, at times like the current one, the PE multiple starts pricing in a rebound, i.e. a ‘Karan-Arjun moment’. We see, say a 30x PE, thereby a market capitalisation of 30x14 = Rs 420.

Now imagine, unlike the recent past, Karan-Arjun are for real and just like in the reel they are slow-cooking somewhere and a confluence of factors like benign macro on domestic and global front, ample liquidity, low interest rates, deleveraged corporate balance sheets, relatively clean banks, supportive government agenda, realisation like “it’s the economy, stupid” and so on result in their actual arrival.

Like it did in the period from 2003 to 2008 when nominal GDP growth was consistently 14-15 per cent and corporate earnings actually grew 25 per cent on year. Going back to our example, the Rs 10 EPS could actually rise to Rs 25 and when that happens the PE multiple at the beginning of the cycle would rightfully present itself even in the late stage of the cycle – this time appearing more believable basis the 5 years EPS growth track record – albeit less bankable compared to beginning of the cycle when not much was priced in (we would realise, in hindsight) versus now when a lot would be priced in (but we wouldn’t know how much!).

But markets would believe Karan-Arjun are here to stay. Now, on Rs 25 EPS, we would probably see 30x PE multiple again or deservedly higher and the market capitalisation would reach Rs 750 or higher with the index potentially near doubling. This is what a ‘Teji’ in the economy looks like. Just because you may not have seen one or may not remember what and when you last saw it, does not mean it doesn’t exist or it cannot happen.

Don’t let your recent past experience inform your view of the possibilities and next time someone tells you market is over-heated or points to the imminent crash in the markets – just ask them – “Have you seen a ‘Teji’? Chances are, they have either not seen one or they have forgotten what it looks like.

This blog also appeared as a thought piece in Outlook Money on 3rd May 2021.

Dipojjal Saha, Portfolio Strategist, contributed to this blog.

(WhiteOak Capital Partners Pte. Ltd)

(WhiteOak Capital AMC)

(WhiteOak Capital Management)

(WhiteOak Capital)

(WhiteOak Capital AMC)